The realm of historical fiction is unique among the genre of fiction. Simply put, other genres act as portals, sending a reader away on an adventure of some kind.

Historical fiction is a time machine.

With a deft hand, a writer can have the reader following the main protagonist as they stand on the deck of a pirate ship blasting cannons into the bows of an enemy vessel. Another turn of the pen, and we’re sent to the Colosseum, our eyes drawn to the spectacle of the arena, as gladiators fight for survival against lions, bears, and other foe on two or four feet. Still, with the turn of a page, we can step into the footprints of a warrior climbing the stairs to a massive stone temple, lavishly painted in symbols of his culture as he stands before his god in worship.

The whole point of historical fiction is to be transported to another time and place.

Capturing the landscape of the past is an acquired skill set, one I believe grows over time. Unlike speculative fiction, historical fiction uses conduits already set in our world. Understanding the cultural biases of the time, along with technology, language, historical dress, etiquette, political, religious, and other socio-economic tenets help develop texture of the world, while giving way to creative license.

It’s important to know that every writer who has ever written, writes to a contemporary audience.

At times, historical accuracy can clash with modern sensitivities. The question then becomes, do I remain historically accurate, or do I cater to modern sensitivities? This doesn’t have a straightforward answer, but that’s common of human nature.

Peeling back the curtain on time gives us an opportunity to study what once was modern, and normal. In history, there weren’t that many dukes about. In 18th century France, there were only thirteen dukes. That’s it. But, as one British author put it, only in historical romance do dukes outnumber the servants. And never, ever, would a duke marry a woman who wasn’t of noble birth. He may run around with the servants, sire illegitimate children, but never would he sully his blue blood with commoners.

However, historical romance has all sorts of dukes marrying nurses, governesses, and… strumpets even! The gall!

Here, the modern reader allows for the blatant inaccuracy because we understand, in part, that it’s just fiction.

Or do we?

What about those unsavory bits of history — normative racial discrimination, the lack of women’s rights, class divides that prevented others from moving up in life?

These bits we don’t like to talk about or think about. Most people, in our time, would find it abhorrent to refer to individuals of minority groups by racial slurs. In the ‘60s, it was quite common.

There was no societal understanding of marital rape. A man couldn’t rape his wife as she was his wife — his property and chattel to do with as he will.

Eugenics was a scientific understanding that certain ethnic groups were naturally better than others.

The idea that a child’s innocence should be preserved wasn’t even a concept. In fact, children were seen as little adults. It wasn’t unheard of for a young girl of twelve to be married to a man of thirty, forty years.

If we were to write books that dealt solely with historical accuracy, some books would never be written.

There’s something to be said for modern sensitivities for it isn’t all about censorship. Modern sensitivities allow for the writer to explore the history while utilizing creative license to show that viewpoint, whatever it is, and show a modern, contrasting understanding of it

In my historical romance, A Bride for Wen Hui, I spent hours researching the role of women in Chinese culture. China’s rich recorded history goes back thousands of years. There wasn’t any way I could incorporate all the nuances in a short book, so I focused on women and foot-binding. I discovered a feminist named Qiu Jin who advocated for women to have the freedom to marry, freedom of education, and abolishment of the practice of foot binding. Although the story doesn’t follow her life, my book was inspired by it

In the historical novel, The Good Earth by Pearl S. Buck, she shows these cultural elements in our main protagonist, who started off as a poor man with one wife and ended up as an old rich man with three wives. Of note, from what I can remember, she never spoke about foot-binding in detail. In fact, in the book, there is a scene where, as the main protagonist becomes disgruntled with his wife, he looks at her and says, “Why are your feet so big?” By this time, he was seeing the woman who would eventually become his second wife. She, horrified he finally noticed her big feet, hurriedly binds her daughter’s feet though this is never explicitly expressed. This seems to suggest that the author saw the matter as a private one, making no judgments.

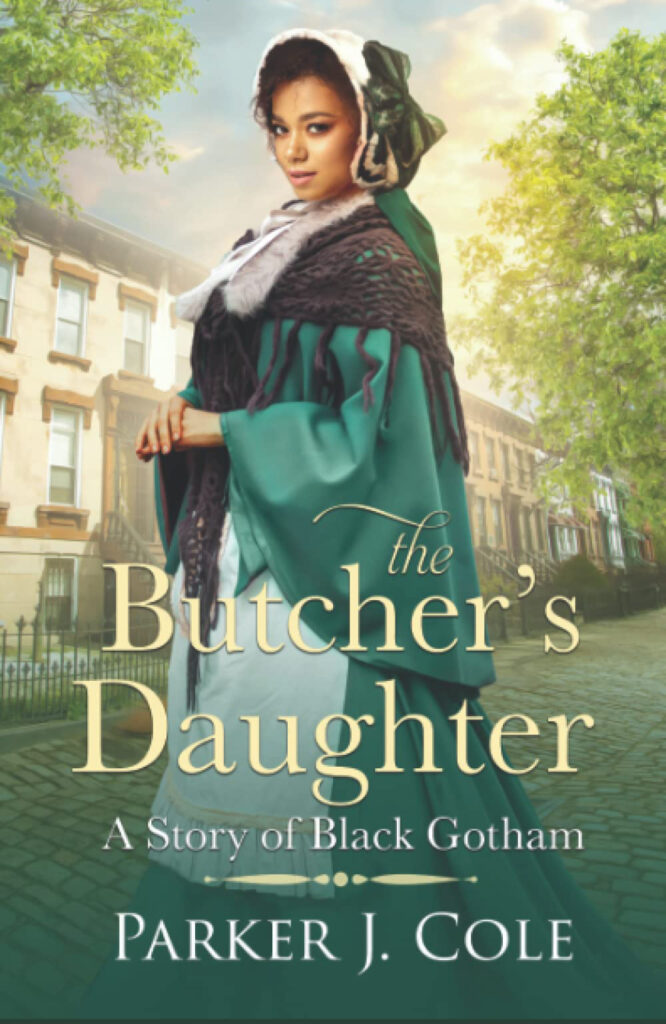

My historical romantic fiction book, The Butcher’s Daughter, was inspired by a non-fiction book called Black Gotham: A Family History of African-Americans in Nineteenth Century New York by Carla Peterson.

Professor Peterson’s book spans her family history which is encompassed by the historical period of the 1830’s through the 1880’s in New York. In the foreword of her book, she mentions black people of the time referred to themselves ‘colored’, ‘Negro’, ‘colored American’, ‘African American’, and ‘Black’. She went on to further state that in this narrow slice of life of the Black elite, they shared mixed ancestry, and some saw themselves as ‘Colored Americans’, seeing themselves in a cosmopolitan view.

I put an author’s note in the front of the book so that any reader who buys it can understand why I used the term ‘colored’ as I did. This can aid in giving the modern reader forenotice of what to expect.

So how do historical fiction writers balance historical accuracy with modern sensitivities? It depends on the message you want the reader to glean. Some books are descriptive, showing life in a single moment of time. Others want to show a change of thought from the character’s POV. Still, others just want to tell a story within the framework of time.

If your protagonist is the hero, even if they grow into that persona, make sure that is set at the beginning. To use the examples I mentioned above, the hero/heroine is the one who rescues the young girl from a marriage. The scientist is forced to doubt his hypothesis when he sees something that bucks against his bias. The husband accepts when the wife says not tonight.

There are many other ways to balance historical accuracy and modern sensitivities. Be prayerful about it all, regardless of what it is.

And make sure you write a good story.

An off and on Mountain Dew and marshmallow addict who writes to fill the voice the sugar left behind. She is an Author, Speaker, Host of The Write Stuff and the Parker J Cole Show, and CEO of PJC Media Worldwide Network.