Fairy tales do not tell children dragons exist. Children already know dragons exist. Fairy tales tell children that dragons can be killed. —G.K. Chesterton.

“So, What’s the Deal with the Anti-Christ?”

That’s the question I was asked one night in Walters House, a boarding school dormitory in a respected private school where I was working as an assistant housemaster. It was the 1990’s and Anne Rice’s famous novel Interview With a Vampire had kicked off a golden age of new wave horror fiction. Soon that would meld with fantasy to create the genre we now know as urban fantasy. One of the boys in the boarding house was a huge fan of these stories, reading books with names like Necroscope; another boarder was listening to an album by a band called Deicide (which is Latin for “god murder”), and every time he put the tape in the deck the singer’s voice sounded like a demon’s. Others were international students who came from Southeast Asia and set up idols in their rooms and rocked back and forth trying to predict the results of the Melbourne Cup (Australia’s premier horse race for the non-Aussies in the audience).

And there was little ol’ me, twenty-three years old and born again for only the last three of those. I was determined to witness the gospel to them, but I was also getting a lot of generic Christian advice about what to embrace and what to reject in order to “be holy as your Father in heaven is holy” (Matt 5:48). Horror, science fiction, roleplaying games, martial arts — young Christians were provided printed lists of activities that they had to repent of being involved in because these were paths that the devil would use to corrupt us, or already had used in my case.

This all made for a hard set of early years in my Christian walk. I don’t know how old I was when I first started to like science fiction, but I was seven when my uncle took me to see Star Wars in its initial release and everyone in my family already knew it was exactly the sort of thing I loved. I started watching Doctor Who so long ago, I remember it being broadcast in black and white. So, science fiction and fantasy were already in my blood and bones. And by the time I came to the Lord, I lived to roleplay. But older, wiser believers told me to put it all behind me for Christ. So, I did. I burned my books — in the barbecue out the back one night by myself. The flames got so high they melted the shade cloth over the backyard. My dad was not pleased. But that was what folks told me the Lord wanted and I wasn’t sure for myself, so I chose to trust them and Him and did what I was told.

And that’s a good idea, in principle. It’s even scriptural; if your right eye causes you to sin, pluck it out. Does your hand lead you to sin? Cut that bad boy off and throw it away (Matt 5:30). The author of the letter to the Hebrews doesn’t back down from the strictest standard even for a moment; we must resist sin even to the shedding of our own blood (Heb 12: 4).

For those of you too young to remember, some of these forms of radical repentance were pretty common in the 1980s & 1990s. Newly born-again Christians were encouraged to destroy their records and tapes of mainstream music (because of the silly backmasking scares); same with roleplaying games, because a teenage boy in the US had killed himself after demonstrating an interest in satanism. He had also been into Dungeons & Dragons, so his mother insisted the two were connected. All manner of popular cultural activities were declared to be of the devil and shunned with force. It was called the Satanic Panic.

So that’s the standard I was adhering to (as best I could) and I found myself amongst a bunch of teenagers who were absolutely steeped in this stuff. What was I to do? I prayed a lot and read the scripture. Tried to witness the gospel and generally made a hash of it. And be there for the boys. They were away from home and needed guidance, in faith and in life. Sure, they were pretty self-reliant and didn’t need their hands held for everything, but there’s still a gap between sixteen and twenty-three that a teenager can learn from.

Some of those teenagers were into roleplaying, science fiction and fantasy, and horror. It turned out that was a point of contact I could make with them, and truth was, having given all that away, I missed it somewhat. So, I talked to them about it and told them how I’d loved it all growing up but had given it up when I became a believer.

And so, we come to the night Jamie asked me “You’re a born-again Christian Mr. Barron. What’s the deal with the anti-Christ?”

My answer was the best single sentence I have ever spoken in evangelism in my life (and I still thank God for it). I said, “Well, if you want to understand the anti-Christ, you first have to understand the Christ.”

And then, starting in Genesis, covering sin, the fall, and the need for salvation, I spent about two hours witnessing the gospel to a handful of guys sitting around one kid’s cubicle (the boys had their own little cubicles to sleep and study in) late into a Saturday night. I ended off with Jesus and God’s ultimate plan to reconcile the world to Himself and how the anti-Christ was the devil’s ultimate plan to subvert all that. It was awesome. Jamie had asked his question because the horror books he was into were full of references to the anti-Christ and Hell and demons and Lord only knows what. I’d never been into horror like that myself, but I knew the lingo from my own love of fantasy and sci-fi, and when Jamie told me the frankly awful details of these books he loved, I could understand them. I wasn’t shocked or worried and so he could connect with me in that space.

I don’t know about Jamie, but another guy who was there that night, Nick, cornered me a couple of years later at university and excitedly told me that he had become a believer. He’d had a path to go through to come to Christian faith, but he was adamant that that night in Jamie’s cubicle was one of the most important steps on the path. That’s a fist pump moment in my Christian walk.

When the folks who encouraged me to radical repentance talked about roleplaying games, they talked about a gateway to cults and satanism and suicide. And sure, the only admitted satanist I ever met, I met through roleplaying. But the Satanic Panic caused Christians to flee a space in our culture — a place of stories, novels, and movies, where thousands of young people and many older people go to find their thoughts, to escape their burdens. And we Christians gave that space up; we literally called it the devil’s thing. We said that anyone who went to those genres was following after the devil and the devil ate it up. He turned these genres into his playground.

Have you ever seen how God is portrayed in the fantastical genres? Take horror, for example. If God the creator is even acknowledged, he’s remote, distant, uncaring, and tyrannical — everything Jesus died to prove He was not. Angels are either terrifying engines of destruction champing at the bit to slaughter every human they can or else they are fallen — rebels against God, because God is too mean for their righteous consciences. From The Warhound and the World’s Pain where Satan is fighting against hell and God to preserve mankind, through movies like Legion, Constantine, and The Prophecy, the loving creator God who sent his son to reconcile humanity is the villain.

In sci-fi, religion has been all but banished, portrayed only as the superstitious rantings of cavemen afraid of fire. One of the best science fiction television series of all time, Babylon 5, has a strong hate group of anti-fans, devoted to despising it. I am convinced it is because B-5 portrays a future where not only does religion still exist, but alien races have their own beliefs, as legitimate as humanity’s. Secular humanists have had the run of sci-fi for so long that the prospect of religion surviving in their visions of the future is offensive to them.

And fantasy, my favourite genre, is the worst offender. Pantheism is the norm, and it is always vibrant, diverse, and exciting. Gods show up in these stories, or their followers receive obvious powers from them. Clerics and druids cast spells derived directly from the power of the gods (to borrow the Dungeons & Dragons paradigm). Or else, all gods are evil, only worshipped by mad sorcerers, practicing black rites. Monotheism is folly and Christ is never even mentioned. We were told to give up these genres and the fans there turned their backs on us as we turned our backs on them.

But this is not the gospel that saved me.

My God stepped down and took it all on to make a way to get to me, to all of us. When I go to the scripture, I don’t see a bookish faith, only taught by academic men and women in neat Sunday dress. Or meek and cowardly monks who cringe every time a pagan priest threatens them with a curse. I see prophets running spiritual battles against forces that hold whole cultures in their grip. I see wars, righteous and unrighteous, and God raising up all manner of heroes, from boat builders to near-superhuman soldiers, to fight for and protect his people. This is exciting stuff, and we should see it that way. And I believe we can bring that excitement into these genres.

We need to remember, however, that we are going onto enemy ground. We need to act, and write, accordingly. There might have been a time when a dramatic writing of the life of David or Samson or a similar Biblical figure, might have had broad appeal. If there ever was such a day, it has passed, hopefully only for a season. We must always remember how the genre sees us and our stories — bland, didactic, cheating them of entertainment in the hope of brainwashing them. We can’t just dress the gospel up in chainmail or a spacesuit and expect it to fool them. We also can’t go in with the plan of converting the genre or rescuing the fans out of it. They’ll smell all such lame tactics a mile off and they’ll hate us for it. Like Jephthah and the Gileadites, they will stand at the border and dispatch us if we cannot pronounce their shibboleth the right way. If we only learn the genre to subvert it, they will keep their backs staunchly to us.

The Satanic Panic occurred because “good Christian folk” were persuaded that the devil was coming for their children and these genres were one of the weapons he was going to use to attack them with. But instead of teaching Christian kids how to fight with those weapons — to not be afraid, that the dragons could be slain — the good Christian folk tried to hide the weapons away and told anyone who went near the cupboard that to even look inside was to endanger your soul. When did we become the ones who run away scared? Our Messiah certainly didn’t.

So, what do we do? First, we remember that our Lord has already conquered this world, and every imagined world, and its god (and gods, for that matter). We don’t have to be afraid of any genre. When we go in his name, He promises to go with us. As with all things, we take care. Just as a reformed drug addict can be the best person to help others recover but has to be careful not to be drawn back into addiction, so we have to know the gospel and not be fooled into compromising it to fit in with those whom we hope to witness.

For myself, that means no metaphorical gods in my writings. Tolkien and other Christian writers might be able to include figures who stand for the key elements of the true spiritual world; God the Father, Jesus, the devil, angels & demons. I cannot do that. They are not wrong, but as one man esteems one day above all others and another esteems each day the same (Rom 14:5), so I cannot follow that path. In my stories, and in all my stories to come, there is one God, creator of every universe, and Jesus is his only begotten son, messiah, and redeemer. This way, I never forget in the midst of all my creative world-building, who my saviour is and whose glory I am seeking first in all my writing.

Then I go for it. I give every story the best, most clever, most powerful imagery and plotting I can devise. I let my characters be good and bad, wrong and right. My heroes show mistakes, sins and ungodly emotions, and my villains are sometimes noble — just as it is in real stories. Their pains are bitter, the joys sweet. I remember that my readers did not come to my stories to hear the gospel; I do not shy from its truth or hide its elements in hope of sneaking them through, but neither do I slap them over the head with my faith. I don’t crash the narrative to insert an altar call in the middle. A +1 Bible of Bashing is a magic item that never will show up in my books.

Most of all, I let my readers hear that I can say shibboleth. I want them to know that I have walked on the plains of Rohan and stalked the back alleys of Lankhmar; I have hidden from the sun in the shadows of Arrakis and commanded starships beside Honor Harrington, Han Solo, and Susan Ivanova; I have stood in the throne room in Aquilonia and crossed the wall with the Night’s Watch; I have witnessed the dark summonings of Melnibone and Pan Tang, and quested for Enlibar steel; I have faced kings and sorcerers and monsters, and I know what is best in life. And in my wanderings across a thousand imagined worlds, I have learned only one unfailing truth. There is one creator God and Jesus is his only begotten son, my saviour, and my redeemer.

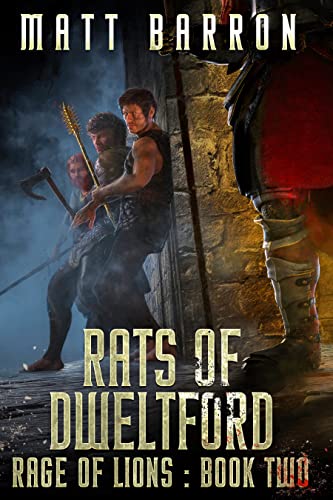

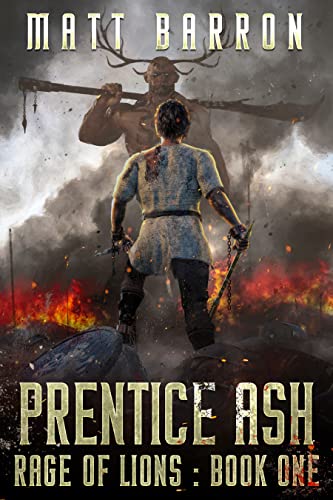

Be sure to check out Matt Barron’s books on Amazon:

Matt Barron grew up loving to read and to watch movies. He always knew he enjoyed science fiction and fantasy, but in 1979 his uncle took him to see a new movie called Star Wars and he was hooked for life. Then Dungeons and Dragons came along and there was no looking back. He went to university hoping to find a girlfriend. Instead, the Lord found him, and he spent most of his time from then on in the coffee shop, witnessing and serving his God. Along the way, he managed to acquire a Doctorate in History and met the love of his life, Rachel. Now married to Rachel for more than twenty years, Matt has two adult children and a burning desire to combine the genre he loves with the faith that saved him.